THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

A new computer program allows researchers to track the formation and migration of all neurons in the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans. The tool, described 3 December in eLife, may help to reveal how autism-linked mutations affect the developing nervous system1.

C. elegans is a familiar model for studying brain function. It has also proven useful for deciphering the roles of candidate genes for autism.

Researchers have already mapped the shape, location and connections of all 302 neurons in the 1-millimeter-long adult worm. But tracking its neural development is tricky. Shortly after forming, the elongating embryo folds and twists into a ball within the egg. This shape-shifting makes it difficult to keep track of individual neurons.

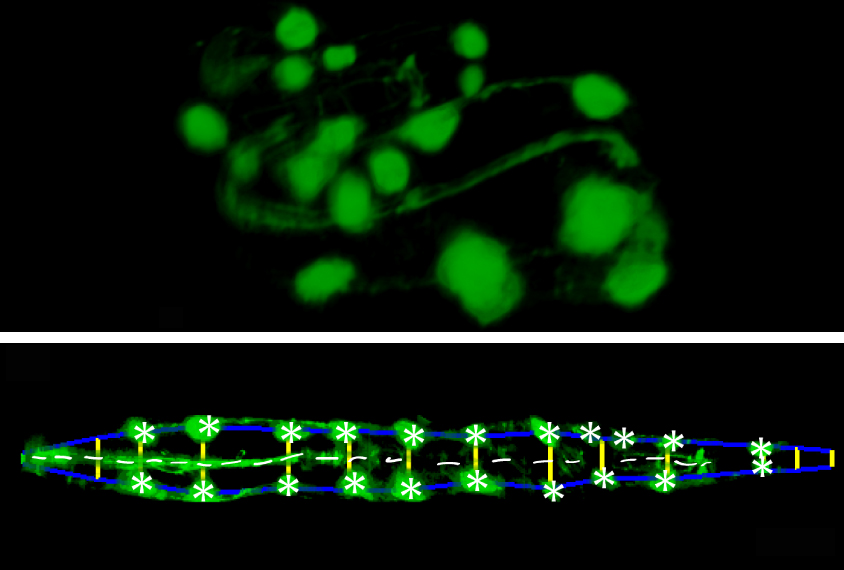

To straighten things out, so to speak, researchers engineered roundworms to express fluorescent tags in certain cells. These tags light up specific points in the embryonic worm’s head and tail and along the perimeter of its body that a high-resolution microscope can capture.

The researchers created software that uses the fluorescent tags in the microscope images to trace an outline of the embryo’s body. The software stitches snapshots from different cross-sections of the embryo into a three-dimensional image. It then computationally uncoils the embryo to make it easier for scientists to track cells of interest.

Moving targets:

To test the software, the researchers engineered roundworms to express additional fluorescent tags in three types of neurons. They then used the software to track the positions of these cells relative to other fluorescent landmarks in images of untwisted embryos at various stages of development.

They found that two of the neurons move in sync with nearby cells on the edge of the embryo. The third neuron moves faster, suggesting that it follows a different migration pattern than the other two. The software also enabled the researchers to monitor, for the first time, the growth of projections from one of the neurons.

Scientists can use the software to track other cell types and structures and generate an atlas of neuronal development in the roundworm. They could also use the tool to explore how mutations, including autism-linked ones, affect development.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.