THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Researchers are grappling with the complexities of transforming oxytocin into a drug for use in the clinic, suggest unpublished results of two studies presented at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Oxytocin is a natural hormone that is involved in social behavior and bonding. Early clinical trials suggest that sniffing oxytocin helps ease the social deficits of autism. But the optimal dose, timing and duration of the therapy is uncertain.

Both new studies looked at chronic administration of oxytocin. “I’m happy to see people are looking beyond a single administration [of oxytocin], because that’s not what’s going to happen in the clinical realm,” says Barbara Thompson, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, who was not involved in either study.

The first study, presented Monday at the conference, hints that the effects of oxytocin linger after treatment ends.

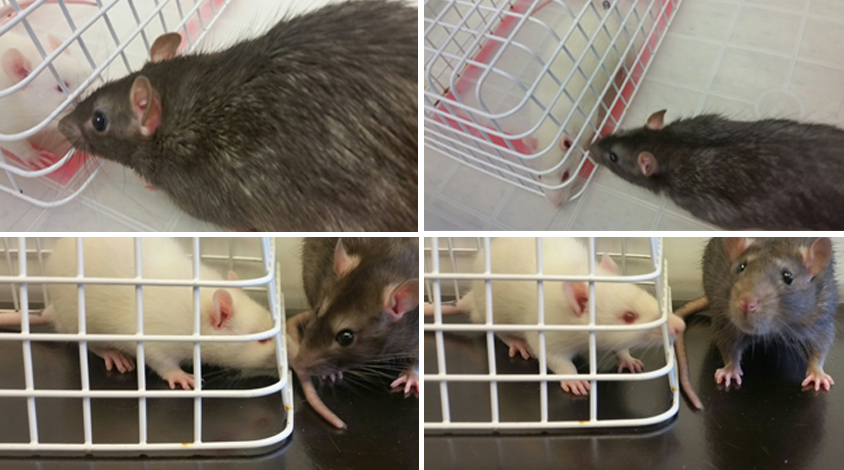

In this study, researchers gave brown Norway rats injections of oxytocin under the skin daily for 22 days. These rats typically have problems with social memory: Unlike other rats, they show no preference for an unfamiliar rodent.

However, after receiving oxytocin brown Norway rats spends more time sniffing a new visitor than a familiar rat, indicating they can now remember and recognize the familiar rat.

Lasting memories:

This effect persists through the course of treatment, although it drops off over time, especially in males. (This phenomenon, in which the same dose of a drug becomes less effective over time, is known as tolerance.)

Surprisingly, the rats still show improved social memory seven days after their last dose of oxytocin.

“This is the thing I find coolest in the whole story,” says Paul Shilling, a project scientist in David Feifel’s lab at the University of California, San Diego, who presented the work. “It most likely means that chronic oxytocin treatment has induced an enduring change in the brains of these animals.”

A few animal studies have looked at the effects of chronic administration of oxytocin but have yielded conflicting results. The fact that the effect lasts beyond the end of treatment is intriguing, says Zsuzsa Lindenmaier, a graduate student in Jason Lerch’s laboratory at the University of Toronto, who was not involved in the work. “I don’t think anyone has looked at that yet.”

But it’s not clear whether the findings would translate to people, Lindenmaier says. “The findings on oxytocin have been quite mixed, even in mouse models,” she says.

Speed bump:

Lindenmaier has looked at chronic oxytocin treatment in three mouse models of autism. Her findings, which she presented today at the conference, sound a note of caution about the hormone’s potential as an autism therapy.

The researchers had the mice sniff oxytocin daily for 28 days, beginning when the animals were 5 weeks old. At 8 to 9 weeks, the researchers assessed social and repetitive behaviors in the mice.

The study included mouse models of fragile X syndrome, mice that replicate a deletion of the chromosomal region 16p11.2, and mice that lack the autism candidate SHANK3.

Grooming behavior in mice is often seen as a stand-in for repetitive behavior in people. Oxytocin treatment increases the abnormally low level of grooming in fragile X mice but doesn’t affect grooming behavior in either of the other models.

In SHANK3 mice, oxytocin causes the mice to perform worse on a test of learning and motor coordination in which the mice have to balance on a rotating bar.

Preliminary analysis suggests that oxytocin has no effect on social behavior in any of the mice.

The researchers also scanned the brains of the mice at 5, 8 and 9 weeks of age. They found that after three to four weeks of treatment, oxytocin alters the volume of seven brain regions including the corpus callosum, hippocampus and striatum.

“That made me think about our study — our lasting effect” of oxytocin administration, Shilling says. “Could some of that be due to changes in brain volume?”

Lindenmaier and her colleagues next plan to compare the mouse data with human data from an ongoing clinical trial of oxytocin. “We want to see if we can find some certain pattern of phenotypes that leads to response to treatment across both species,” she says.

For more reports from the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.