THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

A rare condition marked by a sudden and profound loss of skills is biologically distinct from other forms of autism, a new study suggests1.

The finding is important because the condition, childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD), has been categorized under autism spectrum disorder in the latest version of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM-5) — a decision not everyone agrees with.

The new results challenge the notion that CDD is a form of autism.

“We are finally getting some clues suggesting there might really be some neurobiological differences as well as clinical differences in this cohort of kids,” says lead investigator Abha Gupta, assistant professor of pediatrics at Yale University.

Children with CDD develop typically for three to four years, on average, before experiencing a dramatic regression — often involving motor skills and language — that can last weeks to months. When the children stabilize, they show signs of autism, such as social impairments.

But CDD is typically more severe than classic autism: Children with CDD often have intellectual disability and a significant loss of language.

“[CDD] has distinctive clinical features that sets it apart from disorders encompassed under the autism spectrum disorder umbrella,” says N. Paul Rosman, professor of pediatrics and neurology at Boston University, who was not involved in the new work. “I was disappointed that CDD was not listed as a separate disorder in the DSM-5.”

Private mutations:

To help resolve the debate about CDD’s relationship to autism, Gupta and her colleagues looked at the genes and brain responses of children diagnosed with either condition. The study appeared 4 April in Molecular Autism.

They sequenced the genomes of 15 children with CDD and their family members. They identified 47 genes with rare mutations in the children with CDD — but not in their unaffected siblings. All but one of the children with CDD carry one or more of these mutations, but none of the mutations are common to all the children. “It seems as if they all have their own private mutations,” Gupta says.

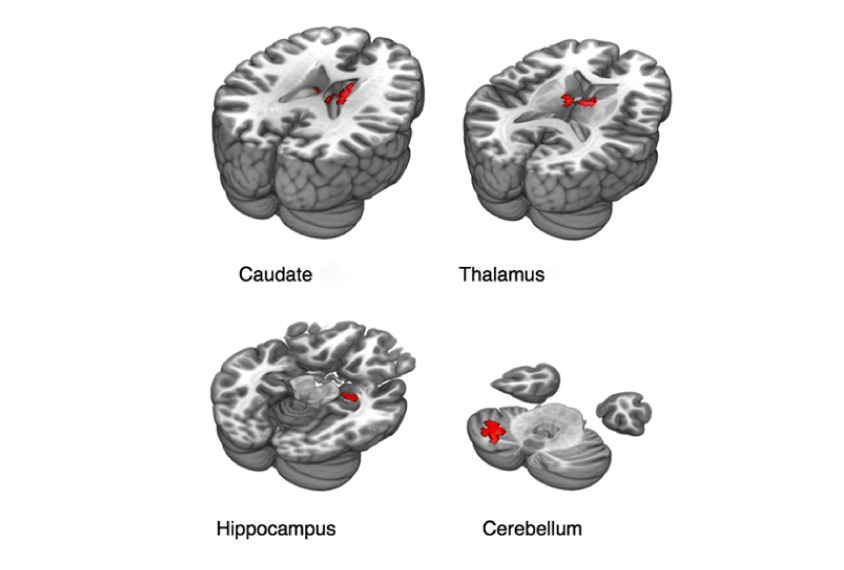

Using the atlas of the human brain transcriptome, which shows where in the brain genes are expressed, the researchers found that the mutated genes are highly expressed in deep brain regions, such as the thalamus and hippocampus. “We were surprised, because autism is mostly linked to cortical regions” on the surface of the brain, Gupta says.

The researchers then used functional magnetic resonance imaging to scan brain activity in the children as they viewed pictures of faces. Only the scans from seven children with CDD were of high enough quality to include in the analysis. The team compared those scans with scans from 21 children with autism and 19 typical children.

The typical children showed increased activity in several cortical brain regions that are known to respond to faces. These include the fusiform face area, which governs face recognition. As expected, children with autism showed decreased activity in these brain regions.

“It very quickly became clear that’s not what we are seeing” in children with CDD, says Kevin Pelphrey, director of the Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Institute at George Washington University, who led the brain imaging.

Early system:

Children with CDD showed no increase in activity in response to faces in the face recognition regions of the cerebral cortex. They did show increased activity in interior brain regions such as the caudate nucleus, thalamus and hippocampus. (They also showed increased activity in cortical brain regions that do not typically activate in response to faces.)

These deep brain regions are responsive to faces in typical infants, but over time, the activity moves to the cerebral cortex, Pelphrey says. In the case of children with CDD, “it looks like we are seeing this early system reemerge, perhaps as a result of experiencing this profound regression,” he says.

The brain regions that become active when children with CDD view faces are the same ones that express high levels of the mutations associated with CDD. “The convergence between results from brain imaging and genetics was very unexpected,” Gupta says.

The researchers next aim to compare children who have CDD with those who have intellectual disability but not autism. This may reveal whether CDD is more like the former than the latter, they say. They also plan to validate their results in a larger number of children with CDD.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.