Westend61 / Getty Images

THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

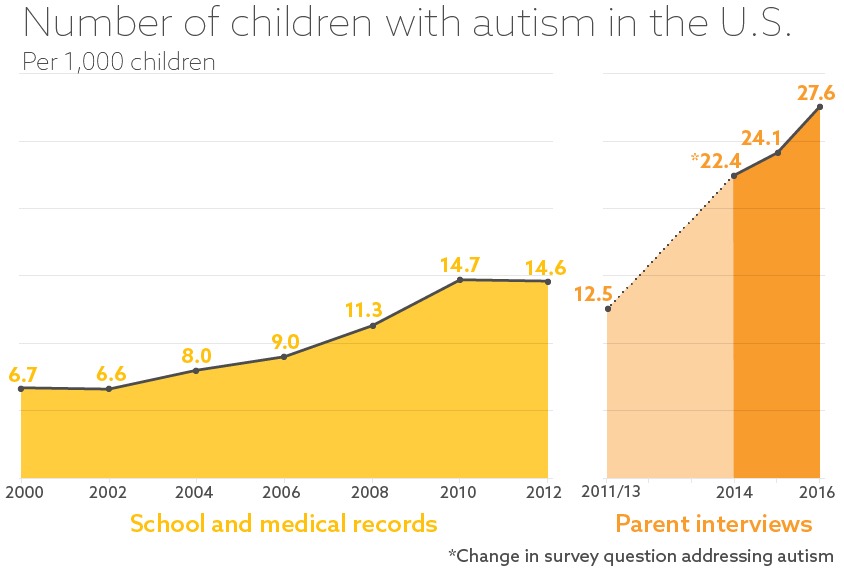

The prevalence of autism in the United States remained relatively stable from 2014 to 2016, according to a new analysis. The results were published 2 January in the Journal of the American Medical Association1.

The researchers report the frequency of autism in the U.S. as 2.24 percent in 2014, 2.41 percent in 2015 and 2.76 percent in 2016, respectively. The new data come from the National Health Interview Survey — a yearly interview in which trained census workers ask tens of thousands of parents about the health of their children. These questions include whether a healthcare professional has ever told them that their child has autism.

The new figures, released by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), represent the highest autism prevalence in the U.S. reported by the agency to date.

“We cannot consider autism as rare a condition as people previously thought,” says lead researcher Wei Bao, assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Iowa.

The peak is likely to result from the fact that the data are based on parent reports. These reports may capture children with relatively mild autism features better than do approaches that rely on medical records, Bao says.

Autism’s reported prevalence in the U.S. has climbed steadily in the past few decades. Researchers attribute most of this increase to changes in how the prevalence is measured, increased awareness of the condition and shifts in the criteria for diagnosing autism.

Reports of autism prevalence worldwide seem to be converging at 2 to 3 percent, says Young Shin Kim, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study.

The new rates jibe with those that emerged from a 2011 prevalence study in South Korea. That study showed that about 2.64 percent of children in one school district have autism.

“I think we are saturating,” says Kim, who led that study. “Whatever study method you are using, it will be leveling off at that point.”

Recent rise:

The new figures come from a nationally representative health survey of 30,502 children aged 3 to 17 across the U.S., including 711 children reported to have autism.

Stable statistics: According to new data, there was no statistically significant rise in autism prevalence between 2014 and 2016.

Graph by Nigel Hawtin

Before 2014, the questionnaire included autism only as one possible response to a question about 10 other health concerns. The updated interview addresses autism in a stand-alone question. The new survey asks parents: “Has a doctor or health professional ever told you that [your child] had autism, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive developmental disorder, or autism spectrum disorder?”

The mention of Asperger syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified is also a first. These relatively mild forms of autism have been subsumed into autism in the current edition of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM-5).

Perhaps as a result of this new question, the prevalence of autism across the years 2014 to 2016 nearly doubled the figure for 2011 to 2013 — from 1.25 to 2.47.

Results from different a CDC survey, released in 2016, put the prevalence lower, at 1.46 percent. In that survey, experts reviewed the medical and special education records from 2012 of more than 38,000 children, aged 8, across 11 states.

Cautious conclusions:

Although figures for both surveys seem to be leveling off, the plateau could be brief.

Estimates based on medical records revealed steady autism rates in 2010 and 2012. But the same method also showed a plateau between 2000 and 2002, after which rates climbed again, says Maureen Durkin, professor of population health sciences and pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Durkin heads one of the CDC sites that assesses prevalence using medical records.

Bao agrees that the latest data are insufficient to be conclusive. “We really need more time to see the long-term trend. It is too early to say that rates have stabilized,” he says.

The new study and Kim’s 2011 study in South Korea both found a similar sex ratio for autism: roughly three boys for every girl. The estimates based on medical records indicate a wider gap: roughly five boys for every girl. The results suggest that girls with autism are sometimes overlooked, Kim says.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.