Brain organoids grown from the cells of children with autism tend to be larger than organoids derived from the cells of their non-autistic peers, according to unpublished results. This difference may reflect the development of neural progenitor cells.

Rose Glass, a graduate research assistant in Jason Stein’s lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, presented the findings yesterday at the 2022 International Society for Autism Research annual meeting. (Links to abstracts may work only for registered conference attendees.)

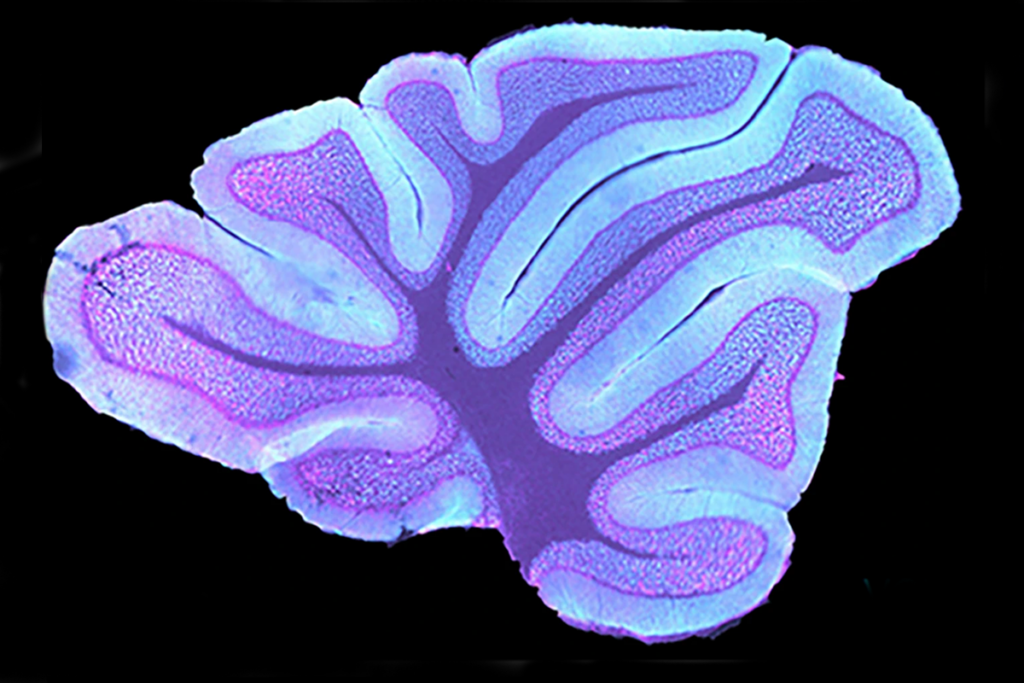

Children with a family history of autism who are diagnosed with the condition by age 2 tend to have unusually fast cerebral cortex growth, a 2017 study showed. The size of the cerebral cortex depends on whether neural progenitor cells differentiate into neurons and glial cells at the appropriate time or continue to divide and produce more cells, the new work suggests.

Glass and her colleagues examined induced pluripotent stem cells derived from non-autistic controls with no family history of autism, as well as those from 10- to 12-year-old autistic and non-autistic participants in the Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS) — including some of the same children whose brains were scanned by MRI in the 2017 study. From these stem cells, the researchers grew 18 cerebral organoids and used RNA sequencing to track their cellular makeup over 84 days.

At day 14, neural progenitor cells from the organoids were in the process of continuing to replicate or transitioning to neurons or glial cells. In the organoids derived from the autistic IBIS participants, RNA sequencing suggested that the neural progenitors were more often replicating, whereas the cells in the organoids derived from non-autistic children tended toward differentiation.

At day 84, the organoids grown from autistic participants’ cells were larger than those from non-autistic participants, in proportions that roughly tracked with the children’s actual cerebral cortex surface area.

According to the radial unit hypothesis, cortical surface area is determined by the pool of progenitor cells, and differentiation reduces this pool. The organoid findings offer preliminary support for that hypothesis, Glass says. The overgrowth she and her colleagues see could be due to the fact that the cells are less likely to undergo differentiation, she says.

Cerebral organoids are simple models of early brain development — and different in anatomy from actual human brains, Glass notes. But these organoids are “a kind of phenocopy” in the way they show either typical growth or overgrowth.

To follow up on this work, she and her team plan to analyze more of the organoids and measure the actual proportions of cell types they contain.

Read more reports from the 2022 International Society for Autism Research annual meeting.