New U.S. autism guidelines call for early treatment

The American Academy of Pediatrics has, for the first time in 12 years, overhauled its recommendations for identifying and supporting autistic children.

Pediatricians should start treating children who show signs of autism even before tests confirm a diagnosis, according to the newest recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics1.

The recommendations, the first overhaul in 12 years, come from a scientific working group in consultation with clinicians and family groups.

Some of the guidelines address known problems in autism services, such as long delays in diagnosis and inconsistent evidence for behavioral therapies.

For instance, the academy now recommends that pediatricians refer children to community services or specialized therapists as soon as signs of autism appear.

This emphasis on early treatment is one of the report’s “exciting and important” elements, says Sarabeth Broder-Fingert, assistant professor of pediatrics at Boston University, who was not involved in creating the report.

Many clinicians lack the time or training to do diagnostic evaluations, says Susan Levy, medical director of the Center for Autism Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who chaired one of the groups that generated the report. And pediatricians often delay behavioral therapies while they await a child’s diagnosis.

“We’re encouraging pediatricians to make referrals” for preschoolers, to give the children access to early treatment and other community services that are not autism-specific, such as physical therapy and special education, Levy says.

The report also calls for pediatricians to monitor conditions that often accompany autism and help families plan for the transition to adulthood.

The recommendations for identifying autistic children remain the same: Conduct regular surveillance for autism traits during routine checkups and perform formal screenings at 18 and 24 months of age. The report suggests that pediatricians should also develop better screens to improve early diagnosis among minority populations and those whose first language is not English.

The recommendations do not call for drastic changes overall, but they are welcome, Broder-Fingert says.

Bureaucratic barriers:

Clinicians may be eager to address the problems outlined in the report, but logistical obstacles such as workload and insurance policies may make the recommendations difficult to implement, Broder-Fingert says.

For example, insurers in many states require an autism diagnosis as a prerequisite for covering therapies for autism. And in some cases, private insurers deny coverage even after a child is diagnosed.

Federally funded services are available to infants and toddlers younger than 3 who are “at risk of experiencing developmental delays,” but federal guidelines define these risks narrowly, and the services are not available to older children. After that age, parents are left with a patchwork of state policies, some of which create barriers to treatment, Levy says.

She notes that families can still find ways to “address some of the issues” that their children may face.

For instance, the report recommends that pediatricians teach parents how to “evaluate the evidence” to determine the best behavioral therapy for their child, Levy says.

But this kind of personalized attention is simply not possible when pediatricians only get to spend 15 to 30 minutes with a family per visit, others note.

“I would be surprised if there are many pediatricians in this country who have the capacity to really support the families the way they need support,” Brodert-Fingert says.

Getting children into occupational therapy, physical therapy or other therapies that focus on speech and language, can help them keep up with their peers without requiring an autism diagnosis, she says.

To that end, her team is testing out ‘family navigators’ — non-specialized health workers who can help families navigate treatment options.

References:

- Hyman S.L. et al. Pediatrics Epub ahead of print (2019) Abstract

Recommended reading

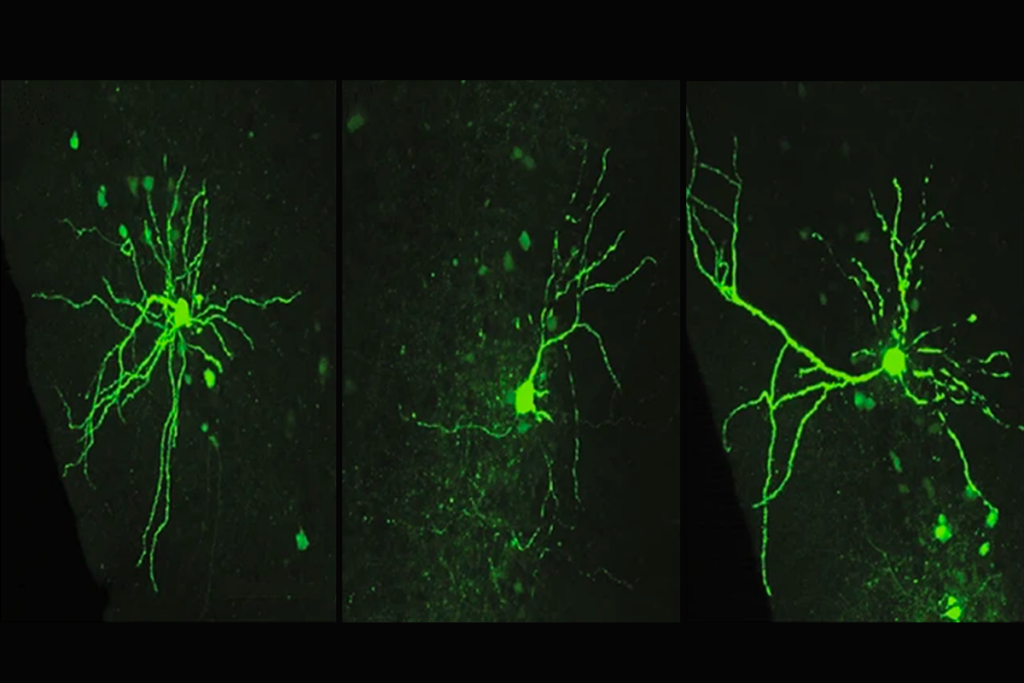

Assembloids illuminate circuit-level changes linked to autism, neurodevelopment

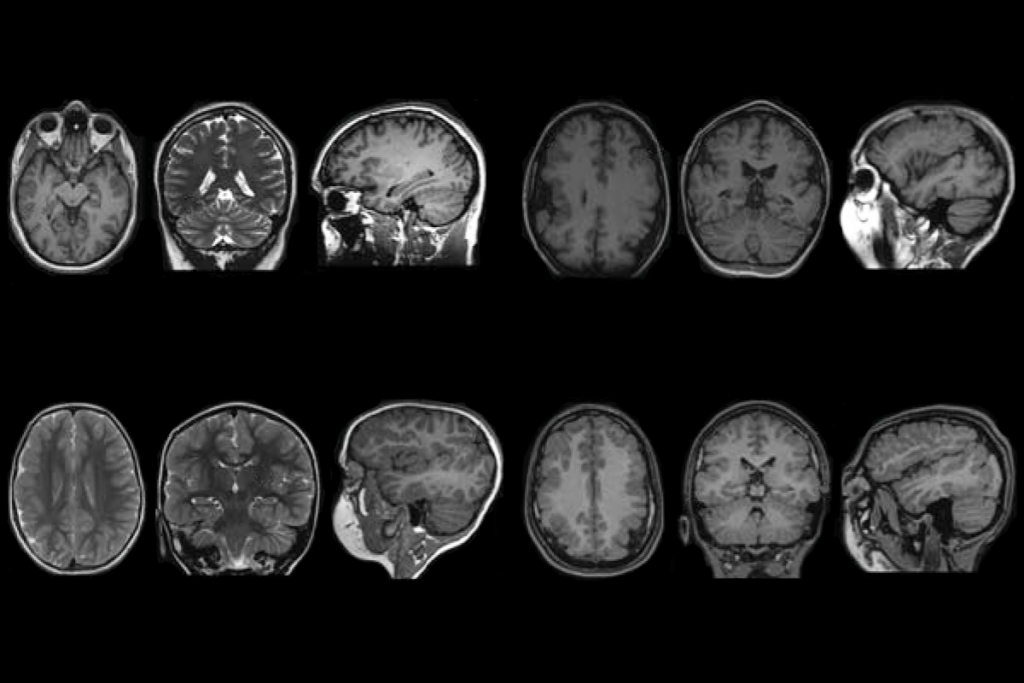

Impaired molecular ‘chaperone’ accompanies multiple brain changes, conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Rajesh Rao reflects on predictive brains, neural interfaces and the future of human intelligence