THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

The drug mavoglurant has no effect on a brain circuit involved in social behavior in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome.

That may explain why the drug failed to improve social behavior in people with the condition, researchers reported yesterday at the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Fragile X syndrome is developmental condition caused by mutations in the FMR1 gene. It is characterized by severe intellectual disability and, in about a third of individuals, autism.

FMR1 encodes FMRP, a protein that is thought to regulate excitatory signaling through one of the receptors for the chemical messenger glutamate. A lack of FMRP, the theory goes, disrupts this regulation, leading to too much excitation in the brain.

Mavoglurant blocks this glutamate receptor, called mGluR5. The drug improves neuron signaling and social behavior in mice missing a copy of FMR1, a popular mouse model of fragile X. But a trial testing the drug in people ended early after researchers saw no benefit.

The new work suggests mavoglurant improves sensory processing and memory in fragile X mice, but not social behavior.

“If you’re looking to improve sensory function, then you might see an effect. But if you’re looking for social improvements, you’re not going to see them,” says Valerio Zerbi, group leader in Nicole Wenderoth’s lab at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, who presented the work.

Insightful imaging:

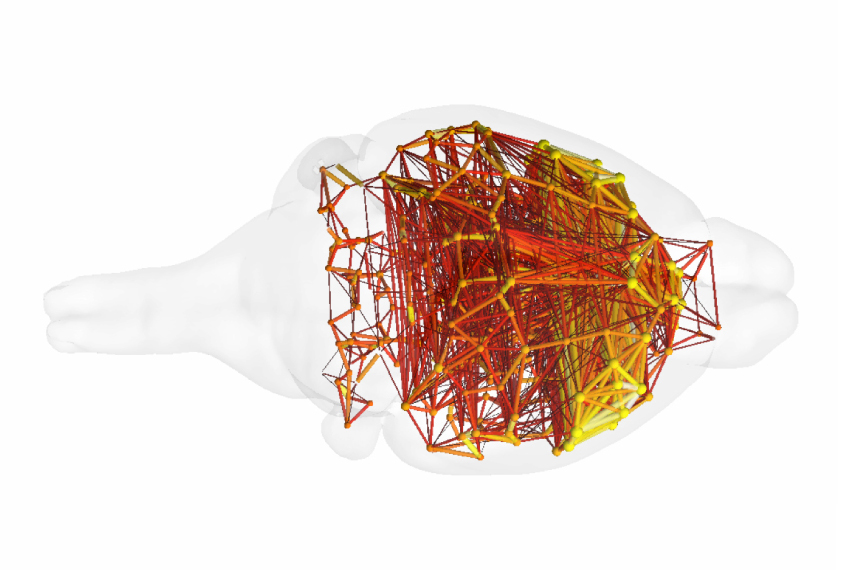

Zerbi and his colleagues performed functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in 26 fragile X mice and 23 controls. The mice were anesthetized during the scans. Half of the fragile X mice received three weeks of mavoglurant treatment in their food; the other half ate food without the drug.

The researchers looked across the brain for regions that became active in sync. This synchrony suggests the regions work together in a circuit. This revealed three brain circuits that are altered in fragile X mice: one that includes the somatosensory cortex, which processes sensory information; one that includes the hippocampus, the brain’s memory hub; and a circuit called the default mode network, which is thought to play a role in social behavior.

Mavoglurant restores the normal strength of the two circuits involved in sensory processing and memory in the mice, the researchers found. But it has no effect on the default mode network.

“When you give this drug, you’re actually only improving two of the three main networks that are impaired in the mice,” Zerbi says.

The researchers measured each mouse’s interest in another mouse over an object, and in a new mouse over one it has seen before. Control mice typically prefer another mouse, particularly a novel one, but fragile X mice do not show this preference. Mavoglurant has no effect on the animals’ preference for a mouse over an object and only a small effect on the preference for a novel mouse over a familiar one.

It is possible that the improvements in social behavior seen in previous mouse studies relate to the drug’s effects on sensory perception and memory, Zerbi says. For instance, mice may be more likely to interact with another mouse when they are not distracted by noises and other sensory stimuli.

The findings highlight the usefulness of studying brain circuits in mice to understand the effects of drugs in the brain, Zerbi says. The approach could help researchers avoid wasting time and money testing drugs that are unlikely to improve behavior in people with the condition.

For more reports from the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.