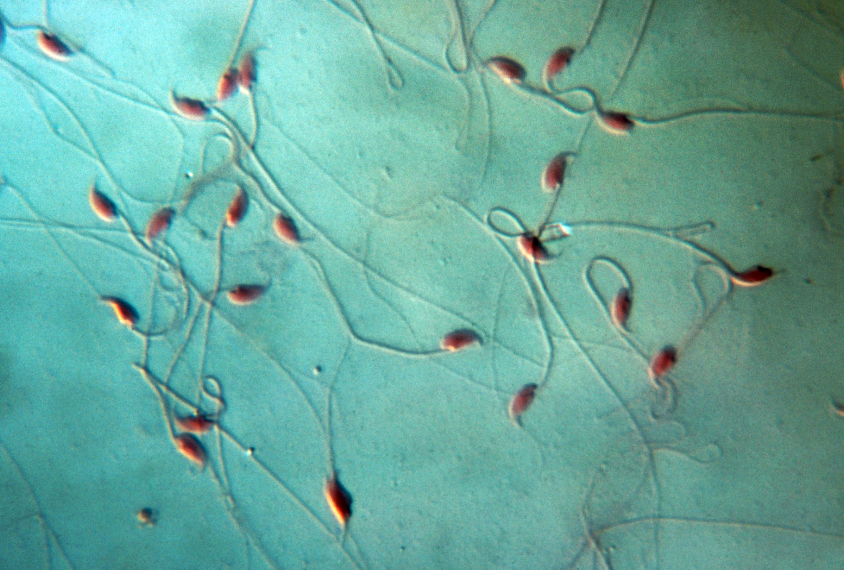

Eric V. Grave / Science Source

THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

The pups of male mice exposed to stress show a muted response to stressful situations of their own, suggesting that environmental effects can last generations. Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago.

The study adds to a line of work exploring the effects of parental stress on the behavior of pups, much of which has been done by Tracy Bale at the University of Pennsylvania.

“We’ve thought a lot about maternal stress, but very few studies have even considered dad,” says Bale, professor of neuroscience in psychiatry. Males may be able to pass the effects of stress down to their pups through epigenetic changes — tweaks in the way genes are expressed. But how long these generational effects of stress last has been unclear.

In the new study, Bale and her team gave adult male mice an unpredictable stream of stressors, such as prolonged light exposure or excessive cage changes, for 4 weeks.

They then bred the mice multiple times over three months to allow at least one cycle of new sperm generation to occur. This flushes out the male reproductive tract, eliminating the possibility of any residual effects of stress on sperm present at the time of exposure.

Stressful circumstances:

At 13 weeks after stress exposure, the researchers bred the mice with females that had not experienced any stress. When the pups of these mice reached adulthood, the team tested their stress response to being restrained in a tight plastic tube for 15 minutes.

Both male and female mice born to stressed fathers show reduced levels of the stress hormone corticosterone in their blood compared with controls. This suggests that paternal stress exposure blunts the stress reactivity of pups.

The findings extend previous work from Bale’s lab showing that the pups of males bred two weeks after stress exposure have a dulled stress response1. These longer-lasting effects suggest epigenetic reprogramming at the level of germ cells, which give rise to sperm.

“There seems to be some kind of permanent effect going on that’s rendering the offspring less responsive to stress,” says Jennifer Chan, a graduate student in Bale’s lab who presented the results.

This reprogramming may be occurring in the epididymis, where sperm become fully mature. In this sperm-storing tube, the researchers found increased levels of nine microRNAs — small RNA fragments that can alter gene expression without affecting the underlying genetic code — previously shown to proliferate in sperm after exposure to stress.

The findings add a level of nuance to the potential role of both paternal and maternal stress in autism risk. However, Bale herself argues against leaning on overblown animal models of disorders such as autism and schizophrenia. Instead, she says, the goal is to understand the processes that underlie the complex effects of stress.

For more reports from the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.