THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Boosting levels of the fragile X protein FMRP in astrocytes reverses features of fragile X syndrome in mice, researchers reported today at the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago.

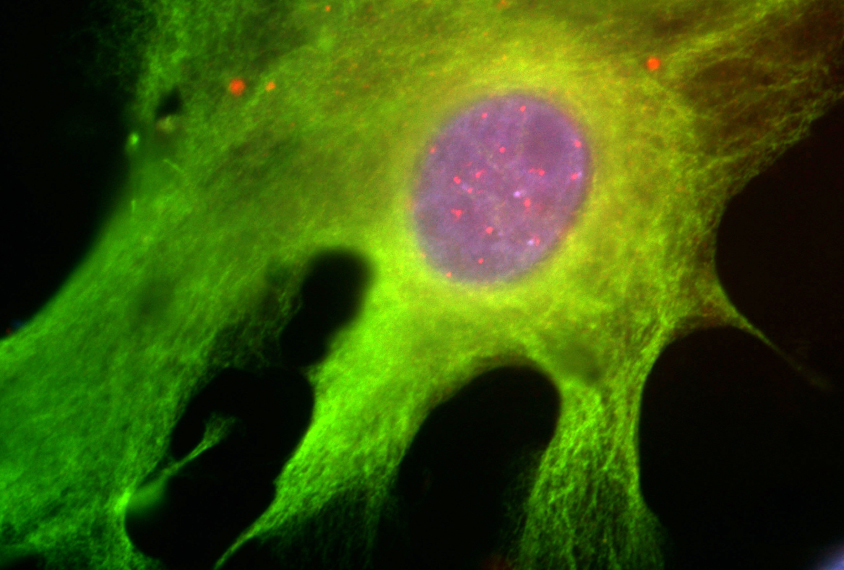

Mice that lack FMRP have brain and behavioral symptoms reminiscent of those seen in people with fragile X syndrome. Restoring the protein’s expression in astrocytes, star-shaped cells that support neurons, reverses these deficits.

The unpublished results highlight the important role of astrocytes in what has long been considered a neuronal disorder, says Haruki Higashimori, postdoctoral fellow in Yongjie Yang’s lab at Tufts University in Boston, Massachusetts, who presented the work.

The findings also open the door to treatments: An approved antibiotic called ceftriaxone mimics the effects of turning on FMRP in astrocytes, the researchers say.

Higashimori and his colleagues reported last year that removing FMRP only from astrocytes triggers fragile X-like features in mice. In particular, the mice show decreased expression of GLT1 — a transporter that helps to clear the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate from synapses, the junctions between neurons. GLT1 levels are also reduced in postmortem brain tissue from people with fragile X syndrome, according to the researchers.

In the new study, the researchers looked at mice that lack FMRP but have a genetic switch that can turn on the protein’s production only in astrocytes. Flipping this switch normalizes GLT1 expression in the brain and boosts the amount of glutamate soaked up from synapses, they found.

Glutamate mop:

The researchers theorized that having low levels of GLT1 in the brain and excess glutamate in synapses would make neurons overly excitable. They reasoned that restoring FMRP expression in astrocytes would help to mop up excess glutamate and lower this excitability.

To test this, they recorded the frequency of neuron firing in the brain’s outer rind, the cortex. Mice that lack FMRP throughout the brain have unusually high firing rates; those with FMRP in the astrocytes show normal firing rates.

Restoring FMRP expression in astrocytes also normalizes protein production, which runs out of control in fragile X syndrome. It also controls the number and length of dendritic spines — tiny neuronal projections that receive input from synapses — which tend to become bushy in mice and people with fragile X syndrome.

To see whether restoring FMRP in astrocytes has any effects on behavior, the researchers measured the movement of mice in an open field. Mice missing FMRP are hyperactive — a feature seen in some people with fragile X syndrome. Turning on FMRP in astrocytes reverses this behavior.

The researchers plan to perform more behavioral tests and take a closer look at the synapses of mice with astrocytic FMRP. They also plan to test the effects of ceftriaxone, which can boost the expression of GLT1 by roughly 50 percent.

“If you can restore even a little bit, it might be very helpful,” Higashimori says.

For more reports from the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.