THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

A drug that blocks a cancer-related pathway normalizes neuron number and prevents behavior problems in mice that lack a copy of the autism-linked chromosomal region 16p11.2. Researchers presented the unpublished results yesterday at the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Chicago.

Loss of 16p11.2 results in intellectual disability, enlarged head, obesity and, often, autism. This region spans 27 genes — including one called ERK1, part of a signaling cascade that regulates cell growth. The cascade, called the RAS pathway, is hyperactive in some types of cancer and in four rare autism-linked neurodevelopmental disorders, collectively dubbed ‘RASopathies.’ The proteins encoded by ERK1 and the related ERK2 gene carry out many of the molecular consequences of RAS pathway activation.

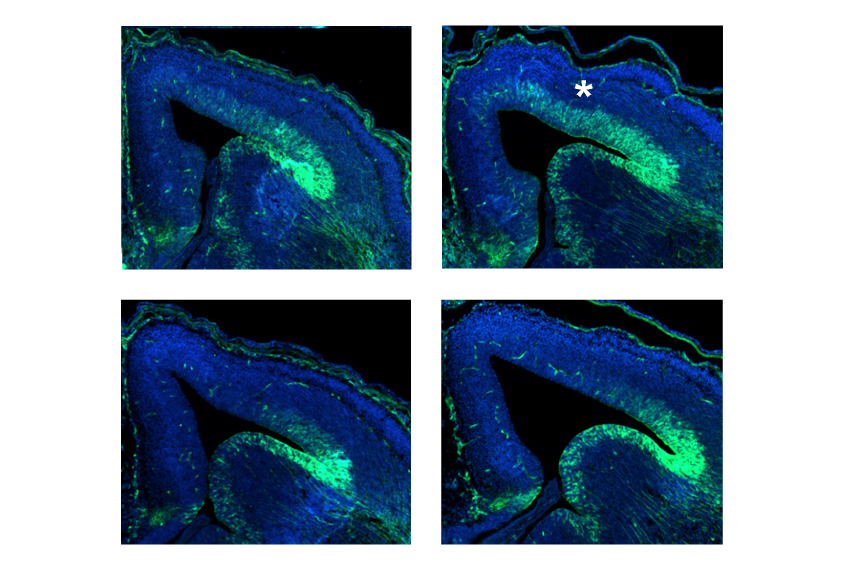

Paradoxically, the ERK proteins are hyperactive in mice lacking a copy of 16p11.21. This hyperactivation coincides with a period of intense neuron development in the mouse embryo. The animals also have too few neurons in some parts of the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer layer, and too many neurons in others.

“Because of this aberrant ERK hyperactivity, we were thinking that we can potentially try to bring the levels down by using a specific ERK inhibitor,” says Joanna Pucilowska, a postdoctoral fellow in Gary Landreth’s lab at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

Sniffing clues:

Pucilowska and her colleagues used an experimental drug that blocks activation of the ERK proteins. They injected the drug into pregnant mice to investigate its effects on neuron development in mouse embryos.

Treating mice with the drug prenatally for five days stabilizes ERK activity, the researchers found. It also normalizes neuron numbers in the cerebral cortex.

The treatment has lasting effects on behavior, too. Unlike untreated mice that lack a copy of 16p11.2 — which are underweight, hyperactive and have memory problems — the treated mice resemble those that do not have the chromosomal deletion.

The researchers discovered for the first time that mice lacking 16p11.2 are quicker than those without the deletion to sniff out a hidden snack in their cage, suggesting they have a highly acute sense of smell, like some people missing 16p11.2. Female mice with the deletion are also faster to retrieve pups that stray from the safety of their nest, an innate maternal behavior. The drug treatment normalizes both behaviors.

Pucilowska says she and her colleagues would like to test the drug in cells derived from people missing a copy of 16p11.2. If it works in human cells the same way it does in mice, then it might be possible to treat people with the deletion using cholesterol-lowering drugs called statins, which are also known to block signaling in the RAS pathway. “This can potentially lead to the first treatment for children with 16p11.2 deletion,” Pucilowska says.

For more reports from the 2015 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.