THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

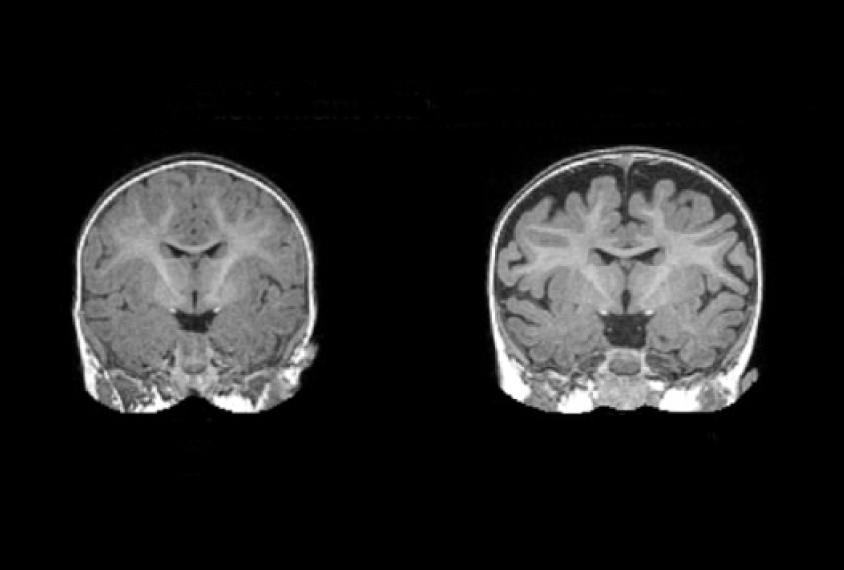

Some infants who are later diagnosed with autism have too much fluid between the brain and skull, according to a study published today in Biological Psychiatry1. The extent of the fluid accumulation at 6 months of age can predict whether a child will be diagnosed with autism at age 2.

The findings point to a possible biomarker that could help doctors detect autism early.

The study “identifies a potential subgroup of autistic individuals with a common biological marker,” says lead investigator Joseph Piven, Thomas E. Castelloe Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Clinicians typically diagnose children with autism around age 4, after observing difficulties in social interactions, along with restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. But signs of autism are likely to be present in the brain much earlier.

In support of this idea, a 2013 study of 55 children in California suggested that 6-month-old infants later diagnosed with autism tend to have excess fluid surrounding the brain. This cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) transports compounds involved in brain growth and, as it circulates, removes waste that could otherwise alter brain development.

The study focused on ‘baby sibs’ — infant siblings of children with autism. Baby sibs are roughly 20 times more likely to have autism than are children in the general population.

In the new study, Piven’s team confirmed the 2013 result using brain scans from more than 300 children at four sites.

“There are virtually no early markers of autism that have been independently validated or replicated in two different studies like this,” says David Amaral, director of research at the University of California, Davis MIND Institute, who led the 2013 study.

Clinicians will need more evidence before they use fluid accumulation to diagnose or screen for autism, however. For one thing, it is unclear whether the excess fluid appears in children with autism who have no family history of the condition. What’s more, only some children with autism show this tendency.

Still, the fluid might be one part of an arsenal of biomarkers for the condition. “A study like this is a critical step in moving the field forward and to ultimately be able to come up with reliable biological methods for diagnosing autism,” says Geraldine Dawson, director of the Duke Center for Autism and Brain Development at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who was not involved in the work.

Fluid finding:

Following the 2013 study, Amaral looked for a large group of children with a family history of autism. He collaborated with Piven and other researchers conducting the Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS), which has magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans and other data from hundreds of children, starting in infancy.

Piven’s team looked at 221 baby sibs and 122 children who have no family history of autism or related conditions. The children all had brain scans at 6 months of age; more than half in each group also had scans at 1 and 2 years old. At all three time points, the researchers assessed the children’s motor, language and visual skills. The IBIS study had tested all the children for autism at age 2 and diagnosed 47 baby sibs with the condition. Clinicians also diagnosed three children from the control group with autism, but then excluded them from the analyses.

The researchers developed an automated method to quantify CSF. They trained a computer to recognize the space between the brain and the skull, and tested the program on scans from the 2013 study. This method yielded results highly similar to those from the 2013 study.

Babies later diagnosed with autism had about 18 percent more fluid outside the brain at 6 months than those without autism, after controlling for brain size, age, sex and clinical site. The excess fluid remained evident at 1 and 2 years of age.

“It’s not easy to do a longitudinal study in children and collect hundreds of images,” says Andrew Michael, director of the Neuroimaging Analytics Laboratory at the Autism & Developmental Medicine Institute in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. Michael was not involved in the new work, but led a study last year that found excess CSF in people with autism ranging in age from 7 to 64 years2.

Predictive program:

Piven’s team entered the 6-month fluid measures from the baby sibs into a machine-learning algorithm to predict which infants would later be diagnosed with autism.

The algorithm honed its own predictive abilities by analyzing data from all but nine of the baby sibs to predict the diagnosis of the remaining infants, and repeating the process 25 times. Ultimately, the computer forecast autism with 69 percent accuracy.

The researchers then applied the algorithm to the 33 baby sibs from the 2013 study. They correctly identified autism for 80 percent of the baby sibs with autism, but incorrectly flagged 33 percent.

The team then looked for features that set apart the subset of children with autism who have excess CSF. They split the group in half based on the severity of autism features. The half with more severe features have significantly more fluid at all ages than the other children in the study. The researchers also found that too much fluid at 6 months tracks with poor motor skills.

Problems with fluid circulation could underlie the fluid accumulation and, with it, a buildup of molecules that alter brain development, Amaral says. But his findings don’t reveal whether the fluid contributes to autism or is a consequence of the condition.

Either way, he says, doctors should not view excess fluid around the brain as benign. “It really may be an indication of increased risk for a neurodevelopmental disorder,” he says.

Amaral says he would like to determine whether excess CSF is specific to autism, or might also signal increased risk for other conditions.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.