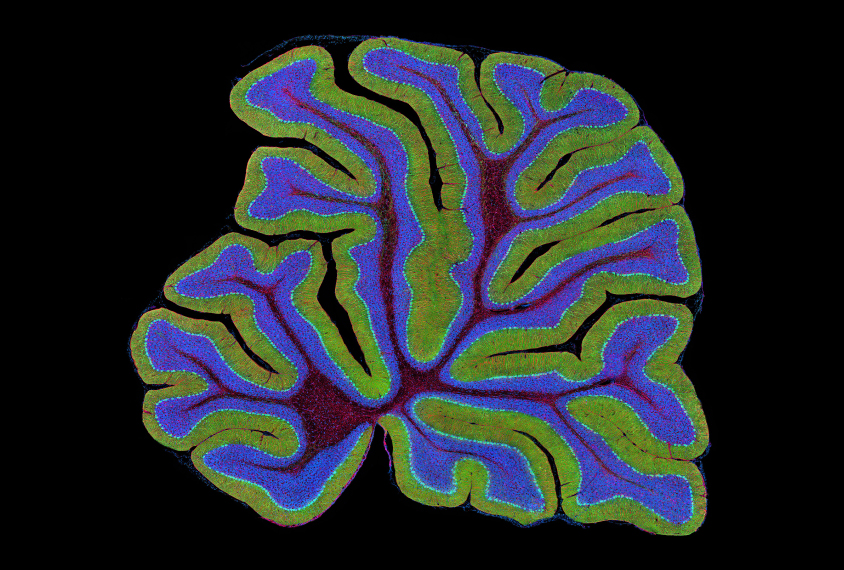

Credit: Science Source

THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

The effects of autism mutations on brain volume might be reversible, even in a mature brain, according to unpublished data presented yesterday at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

The new work focuses on mutations in MeCP2, which lead to a condition called Rett syndrome that resembles autism.

Mice that lack MeCP2 show a range of features, including severe motor and respiratory problems. Studies have shown that restoring MeCP2 function reverses these features in the mice, even in adulthood.

The new study adds to this evidence: It shows that restoring MeCP2 can boost brain volume, which is decreased in the mutant mice, to typical levels in adult mice.

“I think a lot of people have thought that these volume changes that we’re seeing aren’t something we can rescue, because the plasticity of the brain has to come back to make these regions bigger again,” says Jacob Ellegood, research associate at the Mouse Imaging Centre in Toronto, Canada.

The researchers used mice in which MeCP2 is turned off in a reversible way. These mice are born lacking MeCP2, but scientists can restore the gene’s expression at any point. Researchers could use these mice to assess whether a treatment developed for Rett syndrome normalizes brain volume, Ellegood says.

Restoring MeCP2 expression in adulthood is known to normalize several brain features, such as the length of neuronal projections. These studies rely on slicing out small portions of a single brain region, says Rylan Allemang-Grand, a graduate student in Jason Lerch’s lab at the University of Toronto, who presented the new findings. “You’re missing out on information that’s happening across the brain and how it might change in an individual over time,” he says.

Growth spurt:

The researchers scanned the brains of live mice, tracking changes in brain volume across 159 regions over time. They first looked at brain volume in 50-day-old male mice, an age at which MeCP2 mutants typically start to show motor and behavioral problems. The MeCP2 mutant mice have smaller brain volumes than controls do in the cortex, hypothalamus, midbrain, medulla and cerebellum.

The brains of control mice show increases in brain volume from day 50 to day 80, the team found. The mutant mice, by contrast, show a loss of brain volume in several regions. These differences are even more pronounced between 80 and 120 days of age.

The researchers also looked at female mice starting on day 200, when these mice first start to show Rett-like features. (MeCP2 is located on the X chromosome, so the onset of these features is delayed in females because they have a second, functional copy of the gene.) The female mutant mice show a decrease in brain volume that is similar to the pattern seen in in younger males.

The researchers then repeated the experiment in the male mice, switching on MeCP2 expression on day 50. Activating MeCP2 spurs brain growth in a number of affected regions, including the striatum, hippocampus and corpus callosum, the team found.

The volume of two regions, the cerebellum and the medulla, starts increasing rapidly, catching up to control levels by 80 days of age. Others regions, such as the motor cortex, remain constant instead of diminishing in size.

Activating MeCP2 at day 80 also spurs brain growth at roughly the same rate seen in controls during the following 30 days. However, the brain regions don’t reach normal volume because they start off at a smaller volume. Activating MeCP2 in the 200-day-old females also has a small effect on brain growth, but less than in males. This may be because the brain is less able to adapt at that age, Allemang-Grand says.

The results suggest that there is a critical window in which Rett syndrome treatments might be most effective, says Allemang-Grand. Still, the treatments might stall brain alterations even in adulthood.

For more reports from the 2016 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.