THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

More than half of adults with autism in the United States who receive services lack a paying job, and about one-quarter go without critical services such as healthcare, transportation and assistance with job placements, a new analysis reveals.

These findings are among dozens of statistics included in the 2017 National Autism Indicators Report. The analysis is based on responses from state surveys of individuals with autism or developmental disabilities who receive at least one service1.

“There’s this huge chunk of people who get no services, and they’re not attaining any [positive] outcomes,” says Anne Roux, lead researcher on the report and research scientist at Drexel University in Philadelphia.

In 2014 and 2015, agencies in 31 U.S. states and Washington, D.C., sent out a survey to adults with autism or developmental disabilities. Roux and her team analyzed the responses from 3,520 adults with autism or their caregivers. The sample is not nationally representative, Roux notes, because some state agencies did not participate.

The survey found that only 14 percent of respondents hold a regular paid job, and those who do typically work in maintenance and cleaning services. Some adults with autism have jobs in businesses that primarily hire disabled workers. And more than half of adults do unpaid work in this type of setting. Others volunteer in the community.

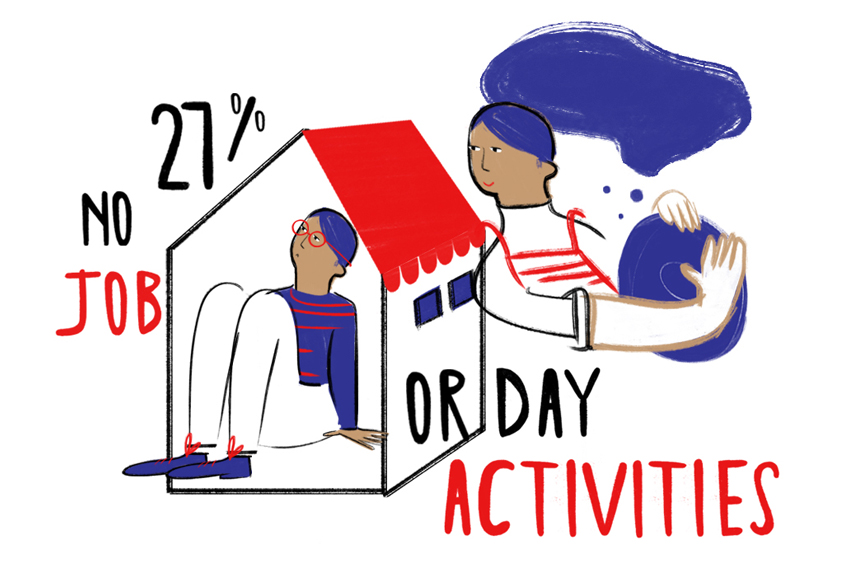

Another 27 percent of respondents don’t have any job — paid or unpaid. “In terms of what they’re doing specifically, I think they’re literally at home, doing nothing,” Roux says.

Many individuals with disabilities want a job or an activity to keep them occupied, the survey showed. For example, half of the unemployed say they wish they had a job. Increased job-support services from the government could address this “mismatch,” Roux says.

Social and cognitive challenges can make it difficult for this population to succeed in jobs, says Shaun Eack, professor of social work and psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the study. As hard as it is for anyone to find a job early in their career, “it’s even more challenging for somebody with autism,” he says.

Independent living:

About 25 percent of adults with autism live in a group home, 10 percent live on their own and 8 percent live in an institution.

Almost half of the adults with autism surveyed live in the home of a parent or family member, but that number varies by age. About 72 percent of young adults live with a relative; among middle-aged adults, that number drops to 21 percent. More than 80 percent of these adults had lived with a family member for at least five years.

This stasis seems to be a general pattern, Roux says. Many people stay put with family members, and many stay stuck in the same job for years. This may be because people with autism are unaware of the choices or opportunities available to them, Roux says.

Even so, 91 percent of the adults with autism reported that they are happy with their living arrangements.

Slightly more than half have a court-appointed guardian, but overall, many of the respondents indicated that they enjoy some independence and a social life: More than 80 percent of adults with autism say they have reliable transportation to get to work or run errands, and almost as many report having at least one friend. Almost half have control over their daily routines.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.