THIS ARTICLE IS MORE THAN FIVE YEARS OLD

This article is more than five years old. Autism research — and science in general — is constantly evolving, so older articles may contain information or theories that have been reevaluated since their original publication date.

Too few or too many copies of a genetic region linked to autism produce similar effects on intelligence and social skills, according to a new study. Higher or lower doses of the gene than normal have opposite effects on brain structure, however.

The study is the first to connect genetic, structural and behavioral data in a single group of people who have variations at the chromosomal region 16p11.2.

Rearrangements of this region are among the most common genetic causes of autism, appearing in about 1 percent of people with the condition. People who carry an extra copy of 16p11.2 or who lack a copy are also at risk of intellectual disability and other neurodevelopmental conditions. But people with the duplication tend to have unusually small brains, whereas deletions lead to brain enlargement.

The new study, published in May in Human Brain Mapping, brings together evidence that these converse variants are associated with similar cognitive and behavioral features but differences in brain structure1.

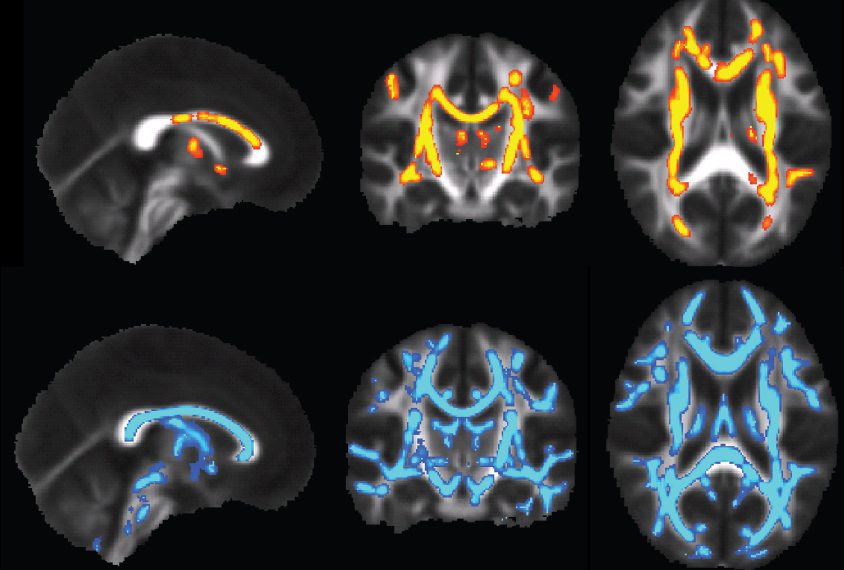

Too many or too few copies of 16p11.2, known as copy number variants, are both associated with changes in the structure of the brain’s white matter, the tapestry of fibers that trail from nerve cells and connect them, according to the new results. This structural shift may lay the groundwork for autism or other conditions.

“There appears to be an optimal white matter architecture,” says senior researcher Pratik Mukherjee, professor of radiology at the University of California, San Francisco, although how the genetic variants perturb that architecture is unclear.

Head count:

The researchers examined the architecture of connections in the brains of 37 children and adults with 16p11.2 deletions, 35 with duplications and 62 controls. They used a method called diffusion tensor imaging, which involves measuring the diffusion of water across nerve fiber tracts.

Using a measure called fractional anisotropy, they found that people with the duplication have underdeveloped white matter, whereas in children with the deletion, white matter is more mature than in typical people of their age.

“The number of copies you have at this chromosomal locus strongly predicts your brain structure,” Mukherjee says.

Mukherjee says the relationship between gene dosage and brain structure is so strong that the researchers could use an individual’s fractional anisotropy score to predict, with up to 94 percent accuracy, whether that individual has too many, too few or just the right number of copies of 16p11.2.

Persistent pattern:

The researchers also assessed the participants’ nonverbal and verbal intelligence quotients (IQs) and evaluated their social ability using a questionnaire called the social responsiveness scale.

The more a person’s white matter deviates from the typical range, the lower that person’s nonverbal IQ and social ability, Mukherjee and his colleagues found. The pattern persists regardless of whether the white matter is much less or much more mature than typical, suggesting that deviations in brain structure — not the deletion or duplication per se — have a bearing on IQ and social skills.

These “intriguing” findings may hold the key to understanding the effects of other autism-linked genetic variants on behavior and cognition, says Helen Tager-Flusberg, director of the Center for Autism Research Excellence at Boston University, who was not involved in the research.

“I wonder whether we might see similar patterns for other copy number variants that can occur in both deletion and duplication variants, or whether these findings are specific to 16p,” Tager-Flusberg says.

People with deletions in a chromosomal region called 7q11.23, for example, have Williams syndrome and tend to be gregarious, whereas people with duplications in that region are reserved.

“This may end up being a general phenomenon,” Mukherjee says.

By joining the discussion, you agree to our privacy policy.