Cannabis compound rebalances signaling to quell seizures in mice

Cannabidiol (CBD) blocks the action of a molecule that drives an overexcitability feedback loop in a rodent model of epilepsy.

Cannabidiol (CBD), a minimally psychoactive compound found in cannabis, alleviates seizures by blocking a signaling molecule that promotes excitation at synapses in the hippocampus, according to a new mouse study. Some forms of autism involve an imbalance between excitation and inhibition, so this research could help to explain why CBD appears to ease some autism traits.

“Excitatory synaptic transmission and inhibitory synaptic transmission are universally found in all parts of the brain, not just the hippocampus, and these types of circuits have been previously implicated in autism itself,” says lead investigator Richard Tsien, chair of neuroscience and physiology at New York University in New York City.

Tsien’s team conducted the experiments using only rat and mouse models of epilepsy, but in 2018 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the CBD-containing drug Epidiolex for two rare epilepsy conditions — Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome — that sometimes co-occur with autism.

Epilepsy is more common among autistic people than in the general population, but not everybody who is autistic has epilepsy. The new findings may be more relevant to the biology of autistic people with epilepsy, or at least those whose brain waves exhibit frequent spikes and sharp waves reminiscent of epilepsy, says Eric Hollander, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, who was not involved in the work.

C

This effect carries the danger that the E:I ratio can veer toward too much excitation, leading to seizures, Tsien says.

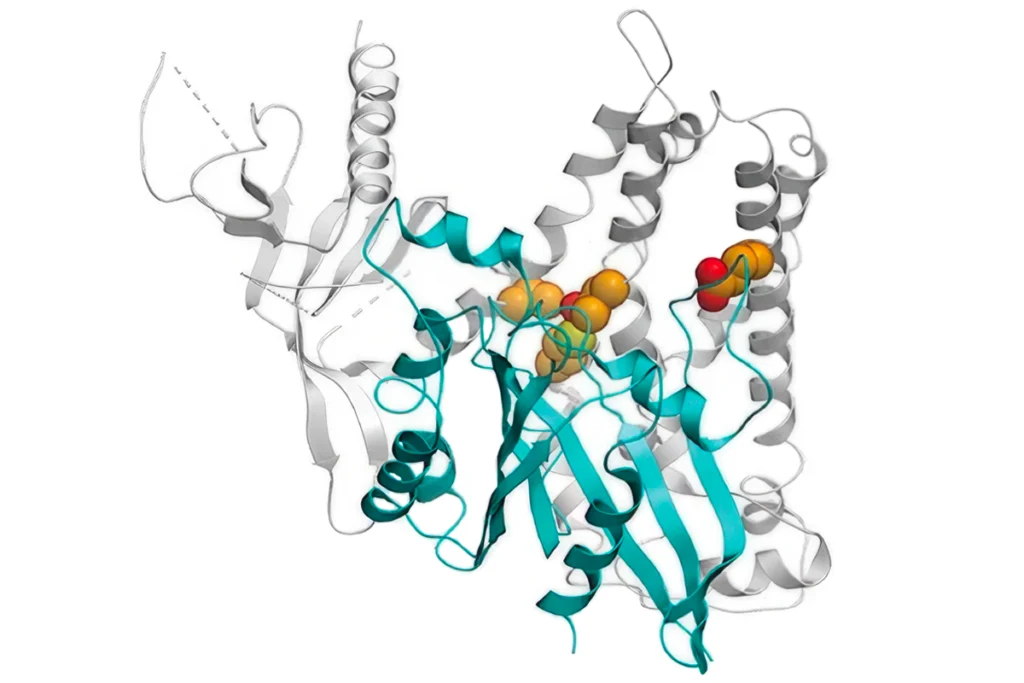

During seizures, LPI levels rise in excitatory neurons, disinhibiting synapses and leading to increased excitation that persists longer than usual, Tsien and his colleagues discovered in mice treated with seizure-inducing drugs. And mouse brain slices treated with LPI immediately increased excitation beyond normal levels and gradually dampened inhibition — a recipe for seizures.

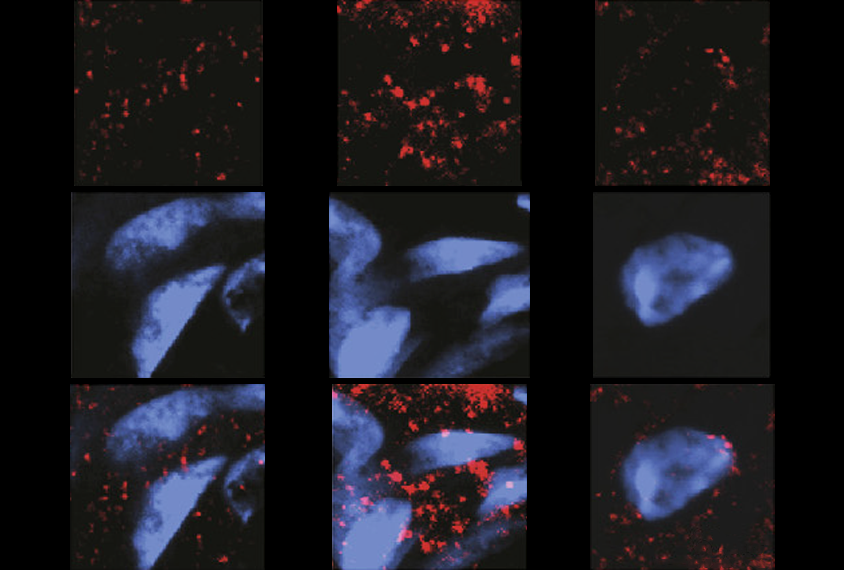

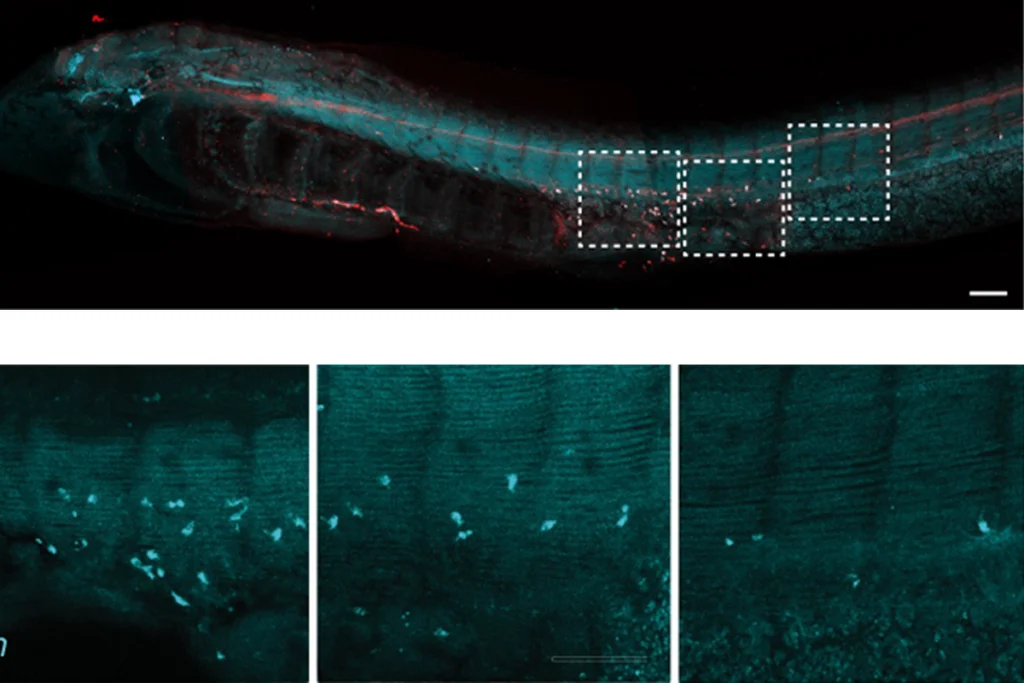

After a seizure, GPR55 is upregulated in two types of excitatory neurons in the hippocampus, according to cell staining of brain slices from mice and rats.

A large dose of CBD blocked the excitatory effects of LPI in wildtype mice and rats, preventing drug-induced seizures. But it had no effect on LPI or seizures in mice bred without GPR55. This discrepancy points to LPI’s effect on GPR55 as a central player in CBD’s ability to alleviate seizures, the researchers conclude.

The results appeared in February in Neuron.

“I am quite convinced that these authors have identified the mechanism of CBD’s anti-seizure properties,” says Graham Diering, assistant professor of cell biology and physiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the study. A big question that remains, he adds, is how CBD affects these synaptic processes over time, as people may be expected to use CBD therapies for years.

Also, the work did not illuminate the exact mechanisms by which GPR55 and LPI metabolism are upregulated after seizures, Diering says, presenting a potential future research question.

L

This finding could explain why benzodiazepines — which encourage GABA to bind to GABA receptors — do a better job of reducing seizure duration when used in combination with CBD than alone, in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome, Tsien says.

The fact that the team induced seizures with drugs limits this work’s direct applicability to people, says study investigator Evan Rosenberg, a neurology resident at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “In real life, you have either a genetic cause of epilepsy or some sort of injury, either a stroke or bleed or [traumatic brain injury], something like that.”

The team focused extensively on the mouse hippocampus, a region important in seizures. To get a clearer picture of whether the mechanisms identified in this study apply to autism broadly, it will be important to see whether CBD can restore signaling imbalances in other regions implicated in autism, such as the cerebral cortex, Diering says.

Even though CBD research in people is well underway, this molecular understanding of CBD’s role at synapses can help build up the base of evidence for the compound and support further work to validate it in people, Tsien says.

Explore more from The Transmitter

New look at lampreys rewrites textbooks on origins of sympathetic nervous system